Unsupervised text classification with word embeddings

Edit – since writing this article, I have discovered that the method I describe is a form of zero-shot learning. So I guess you could say that this article is a tutorial on zero-shot learning for NLP.

Edit – I stumbled on a paper entitled “Towards Unsupervised Text Classification Leveraging Experts and Word Embeddings” which proposes something very similar. The paper is rather well written, so you might want to check it out. Note that they call the tech -> technology trick “label enrichment”.

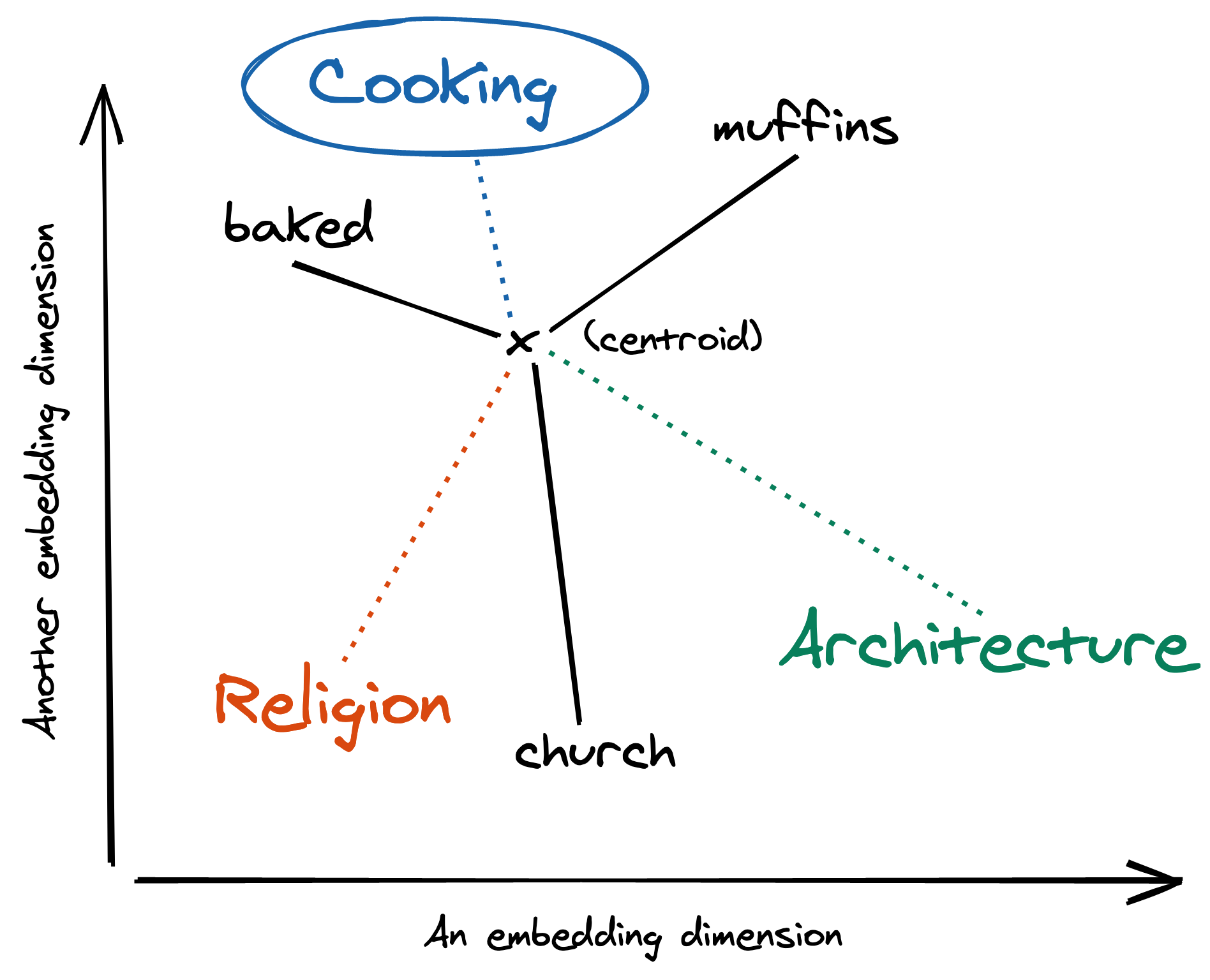

I recently watched a lecture by Adam Tauman Kalai on stereotype bias in text data. The lecture is very good, but something that had nothing to do with the lecture’s main topic caught my attention. At 19:20, Adam explains that word embeddings can be used to classify documents when no labeled training data is available. Note that in this article I’ll be using word embeddings and word vectors interchangeably. The idea is to exploit the fact that document labels are often textual. For instance, the labels from the Toxic Comment Classification Challenge are toxic, severe toxic, obscene, threat, insult, and identity hate. Because the labels are textual, they can be projected into an embedded vector space, just like the words in the document they pertain to. Therefore, a document can be classified by looking at the distance from its word vector centroid with respect to each label. What I’m referring to as centroid is the column-wise average of the word embeddings that are extracted from the document. I believe that a visual example will speak for itself.

Consider the following sentence:

I brought some muffins to church, I baked them myself.

Assuming that we have some function that extracts important words from a sentence, these would be: muffins, church, and baked. Let’s say that we want to assign one of three possible labels to the sentence: cooking, religion, and architecture. The first step is to embed the labels. This can be done by using pre-trained word vectors, such as those trained on Wikipedia using fastText, which you can find here. Next, embed each word in the document. Then, compute the centroid of the word embeddings. Finally, compute the distances from the centroid to each label vector and return the closest one. This particular sentence is assigned the “cooking” label because its centroid is mostly influenced by “baked” and “muffins”, which are close to “cooking” in the embedded vector space.

I think that this is really cool and intuitive! I’m not very experienced in NLP, and so I’m not aware if this is common knowledge/practice. As far as I can tell, in terms of document classification, word embeddings are more often used as the first layer of a neural network architecture. In any case, as Adam says in his lecture, this is really useful for startups that don’t have access to large corpuses of labeled training data. In fact, it turns out that I have a friend who is exactly in this kind of situation. She’s working on some newsfeed project where she needs to classify articles scraped from various websites. She doesn’t have a lot of labeled training data and is thus looking into active learning and semi-supervised learning. These are both worthwhile directions to pursue, but I’m pretty sure that this word embedding method is a low-hanging fruit that she should check out first. Because I’m a nice guy, I decided to code a prototype to help her out. I thought it would be cool to also share this on my blog in order to potentially get some feedback, so here goes.

As a case study, I’m going the BBC news dataset from the Practical Solutions to the Problem of Diagonal Dominance in Kernel Document Clustering paper by Derek Greene and Pádraig Cunningham. The raw text files can be downloaded from this webpage. The documents are organized in directories, with each directory corresponding to one label. Once the data has been unzipped, it can be loaded in memory as so:

import pathlib

docs = []

labels = []

directory = pathlib.Path('bbc')

label_names = ['business', 'entertainment', 'politics', 'sport', 'tech']

for label in label_names:

for file in directory.joinpath(label).iterdir():

labels.append(label)

docs.append(file.read_text(encoding='unicode_escape'))

Note that we’re the storing the document labels, but we won’t be using them to train a (supervised) model. On the contrary, we’ll only be using them to evaluate our (unsupervised) method. That’s the whole appeal of this method: it doesn’t require you to have any labeled training data whatsoever. The first document is labeled as “business” and has the following content:

>>> doc = docs[0]

>>> doc

UK economy facing 'major risks'

The UK manufacturing sector will continue to face "serious challenges" over the next two years, the British Chamber of Commerce (BCC) has said.

The group's quarterly survey of companies found exports had picked up in the last three months of 2004 to their best levels in eight years. The rise came despite exchange rates being cited as a major concern. However, the BCC found the whole UK economy still faced "major risks" and warned that growth is set to slow. It recently forecast economic growth will slow from more than 3% in 2004 to a little below 2.5% in both 2005 and 2006.

Manufacturers' domestic sales growth fell back slightly in the quarter, the survey of 5,196 firms found. Employment in manufacturing also fell and job expectations were at their lowest level for a year.

"Despite some positive news for the export sector, there are worrying signs for manufacturing," the BCC said. "These results reinforce our concern over the sector's persistent inability to sustain recovery." The outlook for the service sector was "uncertain" despite an increase in exports and orders over the quarter, the BCC noted.

The BCC found confidence increased in the quarter across both the manufacturing and service sectors although overall it failed to reach the levels at the start of 2004. The reduced threat of interest rate increases had contributed to improved confidence, it said. The Bank of England raised interest rates five times between November 2003 and August last year. But rates have been kept on hold since then amid signs of falling consumer confidence and a slowdown in output. "The pressure on costs and margins, the relentless increase in regulations, and the threat of higher taxes remain serious problems," BCC director general David Frost said. "While consumer spending is set to decelerate significantly over the next 12-18 months, it is unlikely that investment and exports will rise sufficiently strongly to pick up the slack."

The first step take is to clean the text. I wrote a simple function that does just that.

import string

def clean_text(text):

text = text.lower()

text = text.translate(str.maketrans('', '', string.punctuation))

text = text.replace('\n', ' ')

text = ' '.join(text.split()) # remove multiple whitespaces

return text

>>> doc = clean_text(doc)

>>> print(doc)

uk economy facing major risks the uk manufacturing sector will continue to face serious challenges over the next two years the british chamber of commerce bcc has said the groups quarterly survey of companies found exports had picked up in the last three months of 2004 to their best levels in eight years the rise came despite exchange rates being cited as a major concern however the bcc found the whole uk economy still faced major risks and warned that growth is set to slow it recently forecast economic growth will slow from more than 3 in 2004 to a little below 25 in both 2005 and 2006 manufacturers domestic sales growth fell back slightly in the quarter the survey of 5196 firms found employment in manufacturing also fell and job expectations were at their lowest level for a year despite some positive news for the export sector there are worrying signs for manufacturing the bcc said these results reinforce our concern over the sectors persistent inability to sustain recovery the outlook for the service sector was uncertain despite an increase in exports and orders over the quarter the bcc noted the bcc found confidence increased in the quarter across both the manufacturing and service sectors although overall it failed to reach the levels at the start of 2004 the reduced threat of interest rate increases had contributed to improved confidence it said the bank of england raised interest rates five times between november 2003 and august last year but rates have been kept on hold since then amid signs of falling consumer confidence and a slowdown in output the pressure on costs and margins the relentless increase in regulations and the threat of higher taxes remain serious problems bcc director general david frost said while consumer spending is set to decelerate significantly over the next 1218 months it is unlikely that investment and exports will rise sufficiently strongly to pick up the slack

As you can see, I’ve removed punctuation marks, removed unnecessary whitespace, got rid of carriage returns, and lowercased all the text. The one thing I haven’t taken care of is spelling mistakes. Indeed, if a word is misspelt, then we won’t be able to match it with a word vector. Indeed word vectors are essentially discrete dictionaries that map a word to a vector. This dataset has supposedly been scrapped from the BBC website, and thus shouldn’t contain too many typos. But you never know! A quick win would be to apply Peter Norvig’s spelling corrector, however that goes beyond the scope of this article.

I’m going to be using spaCy for manipulating word embeddings. I’ve decided to use the en_core_web_lg embeddings, which contains Word2vec embeddings that were fitted on Common Crawl data. The embeddings can be downloaded from the command-line as so:

$ python -m spacy download en_core_web_lg

Note that you could use any pre-trained word embeddings, including en_core_web_sm and en_core_web_md, which are smaller variants of en_core_web_lg. The fastText embeddings that I mentionned above would work too. Naturally, the performance of this method is going to be highly dependent on the quality of the word embeddings, as well as their adequacy with the dataset at hand. I’ll get back to this point later on.

The word vectors can be opened with a one-liner:

import spacy

nlp = spacy.load('en_core_web_lg')

I’m now going to define an embed function, which takes as input some tokens – or words, if you prefer – and outputs the centroid of their respective embeddings. I’m going to filter out tokens that are unknown, as well as stop words and those that contain a single character.

import numpy as np

def embed(tokens, nlp):

"""Return the centroid of the embeddings for the given tokens.

Out-of-vocabulary tokens are cast aside. Stop words are also

discarded. An array of 0s is returned if none of the tokens

are valid.

"""

lexemes = (nlp.vocab[token] for token in tokens)

vectors = np.asarray([

lexeme.vector

for lexeme in lexemes

if lexeme.has_vector

and not lexeme.is_stop

and len(lexeme.text) > 1

])

if len(vectors) > 0:

centroid = vectors.mean(axis=0)

else:

width = nlp.meta['vectors']['width'] # typically 300

centroid = np.zeros(width)

return centroid

>>> tokens = doc.split(' ')

>>> centroid = embed(tokens, nlp)

>>> centroid.shape

(300,)

>>> centroid[:10]

array([-0.25490612, 0.3020584 , 0.06464471, -0.02984463, -0.00753056,

-0.15310128, 0.00843642, 0.04468439, 0.02751189, 2.1646047 ],

dtype=float32)

We’re nearly done! The last piece of the puzzle is a mechanism to find the closest label for a given centroid. For this I decided to use the NearestNeighbors class from scikit-learn. But first, I have to extract the embeddings for each label, which can be done by simply reusing the embed function. This makes sense, because our goal is to project the document and the labels in the same domain.

>>> label_vectors = np.asarray([

... embed(label.split(' '), nlp)

... for label in label_names

... ])

>>> label_vectors.shape

(5, 300)

Note that embed expects to be provided with a list of tokens as a first input. In our case, each label is made up of one single word, thus label.split(' ') is equivalent to [label]. If you’re in a situation where a label is made up of multiple words, then you’ll want to split it appropriately instead of treating it as a single word. Anyway, moving on, here’s the code for fitting the nearest neighbors data structure, and searching for the closest label:

>>> neigh = neighbors.NearestNeighbors(n_neighbors=1)

>>> neigh.fit(label_vectors)

>>> closest_label = neigh.kneighbors([centroid], return_distance=False)[0, 0]

>>> label_names[closest_label]

'business'

Hurray, our document got classified correctly! I think that this is quite cool, considering that we didn’t train any supervised model. But I’ve already said that. The $64.000 question, of course, is how well does this perform? Well we can easily process each document with a list comprehension:

def predict(doc, nlp, neigh):

doc = clean_text(doc)

tokens = doc.split(' ')[:50]

centroid = embed(tokens, nlp)

closest_label = neigh.kneighbors([centroid], return_distance=False)[0][0]

return closest_label

preds = [label_names[predict(doc, nlp, neigh)] for doc in docs]

This runs in ~2 seconds on my laptop – note that there are 2,225 documents. We can now use scikit-learn’s classification_report to assess the predictive power of our method:

>>> from sklearn import metrics

>>> report = metrics.classification_report(

... y_true=labels,

... y_pred=preds,

... labels=label_names

... )

>>> print(report)

precision recall f1-score support

business 0.39 0.99 0.56 510

entertainment 0.82 0.52 0.63 386

politics 0.90 0.41 0.56 417

sport 0.94 0.77 0.84 511

tech 0.52 0.10 0.16 401

accuracy 0.59 2225

macro avg 0.71 0.56 0.55 2225

weighted avg 0.71 0.59 0.57 2225

The performance is not stellar, but it is significantly better than random. One thing I thought about is using a different distance metric when looking for the closest label of each centroid. By default, the NearestNeighbors class uses the Euclidean distance, but nothing is stopping us from using something more exotic, such as cosine similarity:

>>> from scipy import spatial

>>> neigh = neighbors.NearestNeighbors(

... n_neighbors=1,

... metric=spatial.distance.cosine

... )

>>> neigh.fit(label_vectors)

>>> preds = [label_names[predict(doc, nlp, neigh)] for doc in docs]

>>> report = metrics.classification_report(

... y_true=labels,

... y_pred=preds,

... labels=label_names

... )

>>> print(report)

precision recall f1-score support

business 0.50 0.91 0.64 510

entertainment 0.76 0.69 0.72 386

politics 0.70 0.74 0.72 417

sport 0.93 0.85 0.89 511

tech 0.85 0.05 0.10 401

accuracy 0.67 2225

macro avg 0.75 0.65 0.62 2225

weighted avg 0.74 0.67 0.63 2225

The overall performance went up by a significant margin, even though we only changed the distance metric. There’s obviously a lot of other things that could be improved. For instance, an interesting observation is that the performance for the “tech” label is very weak. This is pure speculation, but I assume that this is because the word embeddings that we’re using were not trained on a lot of articles pertaining to technology. Moreover, it could be that the tech articles at our disposal contain a lot of niche terms that do not occur in the en_core_web_lg embeddings.

There is one simple trick we can apply to improve the performance for the “tech” label. The trick is to use the term “technology” instead. Indeed, “technology” is more likely to be used than “tech” in a sentence, and thus might have a better representation in the embedded vector space. This may be done as so:

>>> label_names

['business', 'entertainment', 'politics', 'sport', 'tech']

>>> replacements = {'tech': 'technology'}

>>> new_label_names = [

... replacements.get(label, label)

... for label in label_names

... ]

>>> new_label_names

['business', 'entertainment', 'politics', 'sport', 'technology']

The label vectors may now be rebuilt, and the benchmark can be run once more.

>>> label_vectors = np.asarray([

... embed(name.split(' '), nlp)

... for name in new_label_names

... ])

>>> neigh = neighbors.NearestNeighbors(

... n_neighbors=1,

... metric=spatial.distance.cosine

... )

>>> neigh.fit(label_vectors)

>>> preds = [label_names[predict(doc, nlp, neigh)] for doc in docs]

>>> report = metrics.classification_report(

... y_true=labels,

... y_pred=preds,

... labels=label_names

... )

>>> print(report)

precision recall f1-score support

business 0.54 0.91 0.68 510

entertainment 0.78 0.69 0.73 386

politics 0.69 0.74 0.72 417

sport 0.93 0.85 0.89 511

tech 0.95 0.27 0.42 401

accuracy 0.71 2225

macro avg 0.78 0.69 0.69 2225

weighted avg 0.77 0.71 0.70 2225

It works! This goes to show that the exact text used for each label is important. I’m pretty sure there are loads of other tricks to try out. For instance, if you think about it, we’re attempting to classify news articles from the BBC website with word embeddings that were fitted on Common Crawl data, which is quite generic. It seems fairly obvious that a big boost would come from using word embeddings that are trained on similar documents to those that we want to classify. This could be done in a couple of ways, either by training a word embedding model from scratch on our documents, or by fine-tuning an existing set of embeddings. Another thing that is worth paying attention to is the manner in which we compute a document’s centroid. In the current implementation, the tokens contribute equally to the centroid. One could imagine a different ponderation scheme where tokens that appear in many documents contribute less towards the centroid. I recommend checking out this blog post by Sanjeev Arora for further discussion along this path.

I’m not an NLP expert, nor am I particularly fond of it to be honest, so I’m going to leave it at that. The point of this article was mostly to spark an idea and to nicely present it to my friend. If you have some input or have experience working with word embeddings in such a manner, then please leave a comment. If not, keep lurking.